IMPROVING PROCEDURAL JUSTICE FOR THE DALLAS POLICE DEPARTMENT

Procedural Justice establishes four pillars for interacting with community members: fairness in processes, transparency in actions, opportunities for voice, and impartiality in decision making. Our design solution focuses on the delivery approach of the procedural justice training; It is composed of two segments, framing, and engagement.

Dallas Police Department Training Delivery Approach for Lesson Plan

The project asks: “How might we improve Procedural Justice for the Dallas Police Department?” Our overarching “how might we” question guided our research throughout our project as we interviewed key stakeholders about the main challenges and opportunities for the Dallas Police Department when it came to the topic of Procedural Justice. As we conducted further research, our “how might we” question evolved, narrowing its focus on the training delivery aspect of Procedural Justice.

Research Roadmap

We began our process by conducting interviews with eight officers. Our team also conducted a design sprint session with five instructors at the Police Academy. We attended an ABLE training teach back session and for testing our final prototype, we had a feedback session with two of the Academy trainers from the previous design sprint.

From the interviews we conducted with officers we learned:

Training is the main method of delivering any form of knowledge for the department and creates the first impression for procedural justice to police officers.

Resistance to procedural justice training arises from police officers perceiving themselves as doing procedural justice and therefore thinking the training is irrelevant.

The current training is not perceived as framed with the return on investment (ROI) for police officers in mind and is thought of as an academic checklist item rather than actionable knowledge

BLITZ and in-person procedural training have resonated with officers by creating a more personalized and active experience.

Lt. Garcia gave as great insight into officer’s mentality when he shared, “When you put a group of police officers together in a class and you cover certain topics that they are not expecting, or they don't think is going to help them in the real world. You have a lot of a lot of negative comments. [..] What most of these officers will tell you [is] that they want hands on. They want training that they're seeing out there in the street, what they're dealing with.”

Hypothesis Evolution

For our study, the research design was determined by our hypotheses. During the interview process, our hypothesis was: Training is a critical touchpoint for procedural justice. Because of this, we decided to interview with individuals who deliver training. From there our hypothesis began to evolve as we gathered additional data from interviews and secondary research to our second hypothesis which was: Empowering trainers will enable officers to receive better training. This led us to do a design sprint. During the design sprint, we heard feedback from trainers that they appreciated the sentiment, but ultimately did not feel that trainer empowerment was the answer, rather the actual content and how it was framed and engaged. This led us to our third and final Hypothesis which is Delivery is important, but specifically in how it is framed & how it is engaging peers and cops.

Our Solution

From Chief Shaw, we heard how the nature of police work overtime greatly impacts officers, which influences their self-perception and loyalty to protect one another. Related theories such as Belief System Theory and Elaboration, Likelihood Model, and Social Constructivism Theory raise the importance of mentality, framing, messaging, and active learning with peers to enhance the learning experience and knowledge retention. In addition, we used research methods of semi-structured interviews, the ABLE training observation, and our design sprint session. All these sources led us to create our training delivery approach.

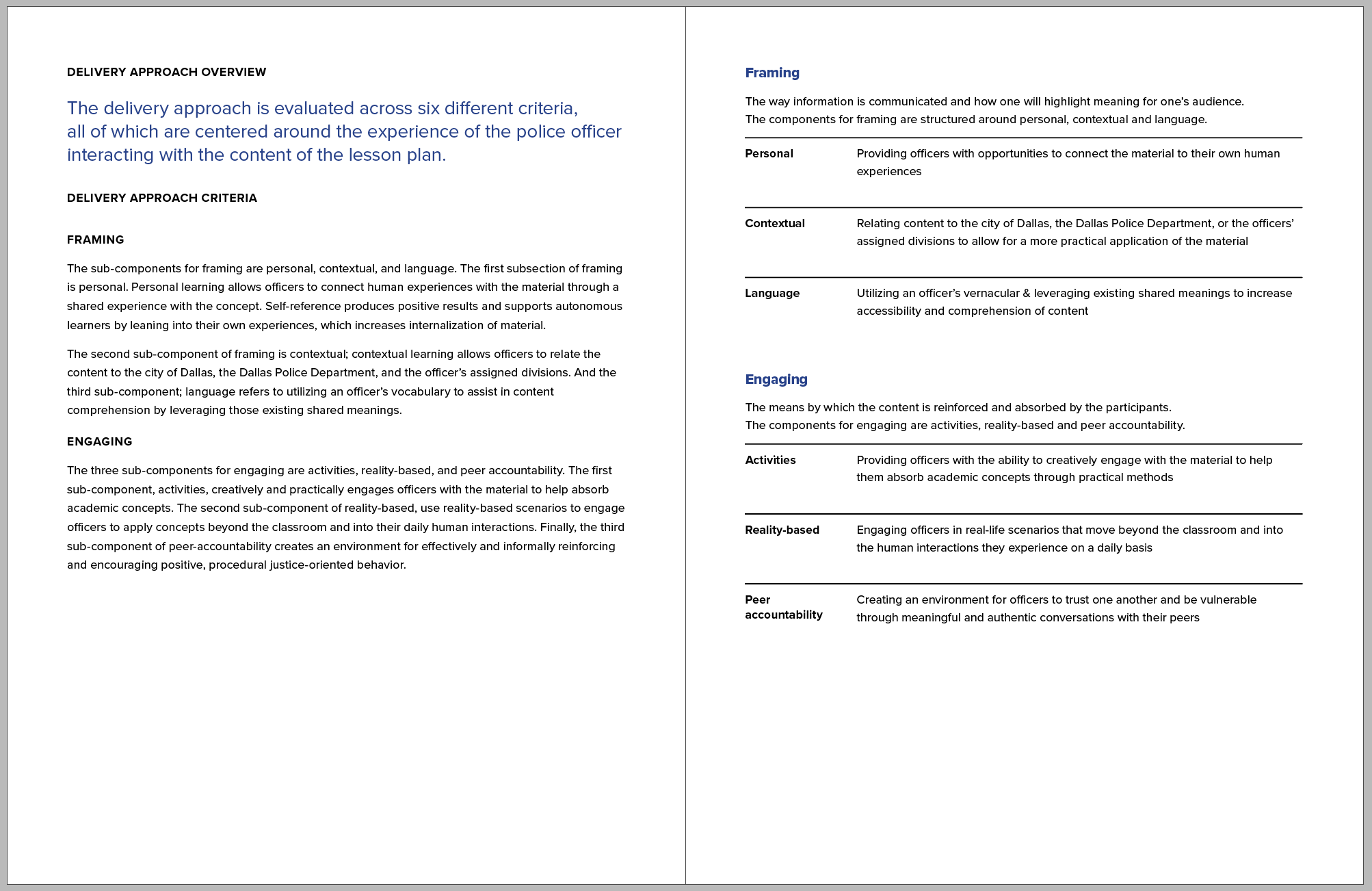

The delivery approach is composed of two segments, framing, and engagement; each of these two components has three sub-components within. Framing aims to center police officers as the audience in the context of any training. Engagement requires the translation of academic concepts into accessible language and practicable activities. The delivery approach allows the Dallas Police Department to evaluate whether the training reaches the expectations for engagement and framing, creating a more meaningful training experience and increasing the likelihood of application of learnings.

Framing

The sub-components for framing are personal, contextual, and language. The first subsection of framing is personal. Personal learning allows officers to connect human experiences with the material through a shared experience with the concept. An example of personal learning would be a discussion question of, “how do you build trust in your everyday relationships with friends and family?”

The second sub-component of framing is contextual; contextual learning allows officers to relate the content to the city of Dallas, the Dallas Police Department, and the officer’s assigned divisions. An example of contextual learning would be describing a scenario that took place in Dallas during a significant current event, such as the protests in the summer of 2020.

And the third sub-component; language refers to utilizing an officer’s vocabulary to assist in content comprehension by leveraging those existing shared meanings. An example of language would be instead of using “Thus, public evaluations of legitimacy influence the degree to which the police have discretionary authority that they can use to function more effectively because the public is likely to give them more leeway to use their expertise,” using “if the community trusts you, they are more likely to listen to you.”

Engagement

The three sub-components for engaging are activities, reality-based, and peer accountability. The first sub-component, activities, creatively and practically engage officers with the material to help absorb academic concepts. An example of an activity would be a discussion around the history of policing with peers.

The second sub-component of reality-based uses scenarios to engage officers to apply concepts beyond the classroom and into their daily human interactions. An example of reality-based would be to review a Dallas scenario of a police encounter and have a discussion on what went wrong, right, and what improvements could be made.

Finally, the third sub-component of peer accountability creates an environment for effectively and informally reinforcing and encouraging positive, Procedural Justice-oriented behavior. An example of peer accountability would be a check yourself activity on how to deal with your emotions and keep your peace. A question asked would be, “What are some things you do to keep your peace while on shift?” Then, officers would be asked to share best practices and tactics with their peers.